By Leigha Dickens, Green Building and Sustainability Manager for Deltec Homes

Last month, I listed common reasons I hear from those who build homes but don’t get them certified through a third party green building certification program—arguing that with certification you end up getting a better house out of the deal. Often this is because of important details that are easily missed and may seem trivial, but can affect energy efficiency, durability, or indoor air quality quite profoundly over the home’s life.

If you’d like to know what I mean by a “better” home, and just what kind of mistakes a green certification program can help you avoid, here are 5 real life problems I’ve seen in new construction. Problems that a green certification program—which requires a third party inspector specifically trained in green building—would have caught.

#1: Poorly Installed Insulation

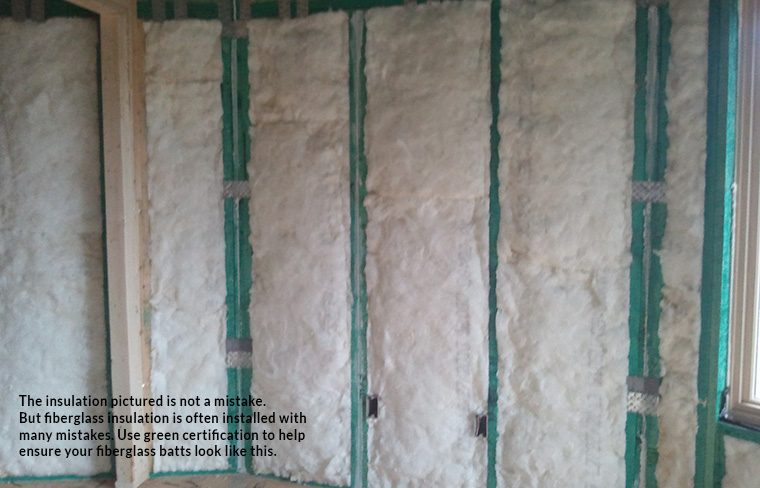

As Green Building Manager at Deltec, clients often ask me about insulation. What kind should I put in? Have you heard about that spray foam stuff? How much should I install? And while those are all important questions, one thing that constantly amazes me is how poorly insulation can be installed, no matter what type or how much of it you choose. Quality of the installation is perhaps more important than type, or quantity. If insulation does not evenly fill a space and has gaps and compressions all around it, or if it doesn’t have the right kind of air barrier (more on those later), it doesn’t actually function at the R-value it’s advertised. That means when insulation is installed poorly, you are not getting what you paid for. Just look at this example from a recent job:

Before: The insulation was installed unevenly. It bugled out in the center with a huge gap behind the bulge, and it is compressed at the corners, without filling the space evenly. This house was being Energy Star Certified, and I knew this would be rejected by the Rater. So I called the installers back and asked them to try again.

After: Insulation fills the cavity completely without gaps or compressions. It is cut to fit snugly around every single outlet, piece of framing, wiring, or other obstacle. When drywall is installed, all six sides of each piece of insulation will be covered with an air barrier.

Unfortunately, insulation installation (try saying that five times fast) quality is something a homeowner has little ability to predict ahead of time, and must rely on their contractor to ensure. But contractors, and often county building inspectors, might not be experts in how to inspect this.

A green certification program wouldn’t let poor insulation installation fly. Energy Star for Homes requires the Rater to inspect all insulation, as do the NGBS, LEED, and NC Green Built Homes. If the installation doesn’t meet the requirements, it has to be done over if you still want to earn the green certification, as was the case in the project above.

#2: Holes in Your House

“Air barriers” are one of those things that building energy nerds love to harp on, but homeowners and even builders don’t always understand what we’re talking about. And if they don’t even know what an air barrier is, it’s easy to see why they might miss installing one altogether in places where an air barrier really needs to be there.

Air barriers are locations within framing where something rigid needs to be installed to keep air from escaping the heated part of the home. When air you’ve already spent energy to heat up has the freedom to simply leave the house, you have to spend more energy heating up more air to replace it. Air leaking out of your house is a significant issue for heating and cooling bills (about 25%-40% of heating and cooling bills come from air leakage, according to the DOE), and installing air barriers is about understanding where, in typical building framing situations, you’re likely to end up with an unintended pathway for air to get out, and putting in something to block it. .

A commonly missed air barrier is in the floor joists above a wall in a basement that separates a deliberately unheated space—perhaps a garage—from heated space, such as your extra bedroom and your pool table den. The dividing wall between the heated and unheated rooms gets built and insulated, but it often stops at the floor joist itself.

Yes, this picture has fiberglass batts stuffed into the ceiling, but fiberglass does nothing to stop air movement. Cold air can move right through these open floor joists and into the heated living space from the unheated garage. The solution, to make this house appropriately air-tight, is to install something rigid, air-tight, and sealed in these openings in the floor joists, like in this example where foam board is fitted into the floor space and the corners are sealed with canned spray foam:

While holes like this would undoubtedly show on a blower door test as big sources of air leakage, if all you do is test at the end, it may be too late. That’s why Energy Star for Homes has an entire air barrier checklist that must be followed—and inspected by an Energy Rater, so that a detail like this could not be missed. Green Built Homes in NC follows the same Energy Star checklist, while LEED awards points for air barrier detailing. Critically, this inspection must occur before drywall is installed to better see such locations that might otherwise be left invisible to the homeowner forever, making them wonder later on why their basement is so cold.

#3: Problematic Pairings of Technology

Today’s homes are being sold with more upgrades, new technologies, and higher end features than ever before. Many of these features are even advertised as being quite green, such as high-performing spray foam insulation, or a charming wood stove. But sometimes seemingly unrelated features can have unintended consequences when used together in the same project without care.

One example: combining spray foam insulation, a large commercial-kitchen style gas range, and a wood stove in the same home. Individually each of these items have their benefits and considerations. Spray foam insulation is an exceptionally air-tight insulation that can be easier to install in funky spaces without those unfortunate gaps and compressions (and it makes a good air barrier!), so is often an energy efficiency upgrade that makes sense. Commercial style gas ranges are something I might talk you out of, but are a popular feature for folks who love to cook. And wood stoves can be a romantic source of ambiance and backup heat.

Yet putting these three upgrades together in one home can create a serious indoor air quality problem. Spray foam insulation tends to make a house extraordinarily air-tight. This is a good thing, encouraged and rewarded by green building certification programs, as it reduces the aforementioned issue of conditioned air leaking out of your home. But, an air-tight home can be put under suction more easily by an exhaust fan. Commercial kitchen style gas ranges, for their part, produce considerable heat, fumes, and moisture. A very powerful range hood is typically required to effectively vent all that moisture and fumes out of the house. Yet in air-tight homes, these powerful range hoods can put a dramatic amount of suction on a home. Add in a wood stove, which relies on the buoyancy of hot air to vent its own smoke, and you can have a situation where the suction from the range hood overcomes the wood stove’s ability to vent and pulls smoke and ash particulates straight into your living room. This is a serious indoor air quality problem.

These problems can be avoided when thinking about the whole house as a system, which green certifications require you to do. Many green programs require that wood stoves be suitably air-tight and use a separate outside air intake, increasing their resistance to the high suction created by a powerful range hood. A green program might also require make-up air for your commercial range hood, so that fresh air is brought inside whenever it turns on, reducing some of the pressure. Or better yet, offer points toward higher levels of certification if you switch from a gas range to an induction range, which offers high energy efficiency while also eliminating an open flame and the associated pollutants from your indoor air.

Steam’s path through a common improperly vented kitchen exhaust. If the system is not actually vented to the outside—as would have been required with a green building certification—then trying to vent the steam really just means depositing the moisture on the kitchen ceiling.

#4: Indoor Air Quality Nuisance Issues

Kitchen range hoods that just recirculate steam and grease around the kitchen, or bath fans that don’t really do much to de-steam your bathroom after a shower, are just two indoor air quality problems that Energy Star for Homes happens to solve. For the former, ventilation to the outside is required in the kitchen of an Energy Star home, and for the latter, the air flow on your bath fan has to be tested, and it has to actually work. Otherwise, steam can build up over time, leading to the potential for mold growth.

If indoor air quality is a concern of yours, programs such as LEED for Homes or IndoorAirPlus can make a difference to low-level invisible sources of pollutants as well, requiring or rewarding the use of low-VOC and/or formaldehyde free caulks, sealants, paints, stains, and even interior doors, cabinets, carpeting, and composite wood products.

#5: Indoor Air Quality Serious Issues

Remember that wood stove and powerful range hood example? The problem is wood smoke sucked back into your home. That is a serious problem if you have asthma or allergies, but is not inconsequential for your health even if you don’t.

Other serious indoor air quality issues that might arise if you’re not paying attention include a new home without any kind of mechanical fresh air ventilation system at all. Energy Star for Homes, LEED for Homes, Passive House, and the DOE Zero Energy Ready Program all require whole house ventilation be sized and field-tested to meet ASHRAE62.2, the residential standard for fresh air ventilation.

Or what about mold building behind your walls, due to a window flashing detail that was missed and allows rainwater to sneak into places it shouldn’t? Energy Star for Homes has a water management checklist, and critical flashing details to direct water away from vulnerable joints in a building are mandatory in most other programs as well.

Are you concerned about carbon monoxide—a deadly, odorless and invisible gas that can be a byproduct of combustion and which kills over 400 Americans each year? Green building programs have you covered, typically prohibiting the use of equipment such as ventless gas fireplaces or open wood fireplaces that produce dangerous levels of carbon monoxide, and requiring proper venting protocols for any combustion appliances in your home.

The Bottom Line

Green building programs were created out of need. Someone, somewhere, saw that homes were being built in ways that had adverse impacts on the environment, used more energy than needed, or created unhealthy indoor air or moisture problems that reared themselves far too early in a building’s life. Contractors were missing details, while building codes and standards weren’t keeping up. As the industry has matured—developing more varied building products, systems, and features—code and common construction knowledge hasn’t always caught up to the implications on health, energy, and environment of applying these things together in a home. Voluntary, third party green building programs became a way to inject better knowledge into the industry, and add recognition to those who apply that knowledge to make homes the best they can be. Many reference engineering standards and are based on extensive industry research, are developed or recognized by universally accepted standard-setting protocols, and change as needed based on improved knowledge.

They aren’t perfect, of course. The quest to build homes that have reduced—or perhaps no—impact on the environment, while using as little (non-renewable) energy and keeping the occupant as healthy and happy as possible—is never ending.

But green programs do rely on knowledge we have to date that is better than chaos. At the end of the day, they’re really about applying what has been learned before to make not just the environment, but all of our lives, better.

This blog is part 2 of a 4-part blog series on green building. Check out the other posts in this series:

Part 1: Coulda, Woulda, Shoulda: (Flawed) Reasons Homeowners Don’t Use Green Building Certifications

Part 2: Five Mistakes Green Building Certifications Can Catch

Part 3: The Process of Getting a Green Building Certification

Part 4: Residential Green Building Certification Program Guide