Living in our built environment:

The current world is littered with examples of humans building structures and spaces that meet functional needs or demonstrate its power over nature. From windswept grand plazas to sunless city street corridors leading to soulless grey cubicles lined up in matrixed rows or windowless hospital rooms taken over by the arresting buzz of machines.

In the past few decades, only sparse attention has been paid to bringing nature into our living environments, often through a few sickly house plants stuck in corners or wallpaper left over from decades past.

However, it wasn’t always this way, nor should it be. The more mechanical the world becomes, the more we need to consciously consider and design for a human experience in the world.

Humans desire an innate connection with nature. From the crackling of a campfire, to the soothing crashing of waves, to dappled sunlight through tree leaves and the organic feel of wood, we still yearn for connection with nature for security and health. Recent studies have demonstrated that. While the term biophilic design is relatively new, the concept has been around for centuries.

A new trend with an old approach:

The practice of biophilic design predates the modern world. It was how humans were forced to live together with and dependent on nature.

With the rise of agriculture 12,000 years ago and then the evolution to the concept of the urban environment 6,000 years ago to the more recent history of industrialization, western society has shifted its view to a competition with nature glorifying human accomplishment.

You can see that in the early industrialization with factories built for manufacturing efficiency and architecture that emphasized scale and rigid shapes. So how have recent buildings like the Google headquarters that emphasize greenery and cocoons come about? How did we go from the photo on the left to the one on the right?

It is an age-old concept that has recently found a new home. Some people track it all the way back to the Hanging Gardens of Babylon. For surviving buildings, it really got its start in the Islamic Golden Era (8th-14th Century). During this period, buildings were designed for both direct and indirect contact with the natural world—as they strove to seek out an understanding of the world.

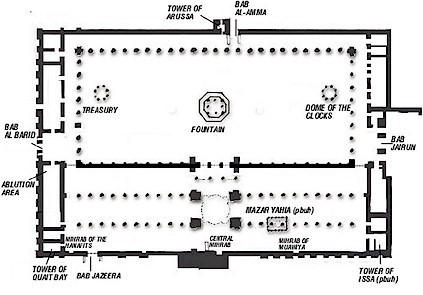

For example, the Umayyad Mosques (Damascus, Syria) built between 705-715 used patterns that were found in nature. While not exclusively used, they were dominant in both art and architecture to avoid the depiction of the human form for religious beliefs.

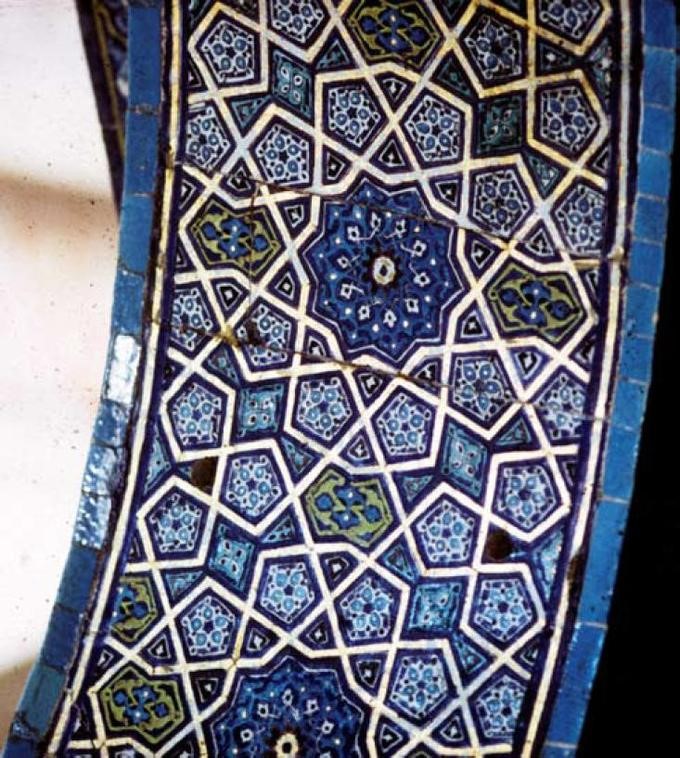

In this picture you can see the natural patterns, natural light, and natural materials used in the interior of the mosque.

While the structure of this Mosque was built as a fortress for protection, the courtyard includes access to nature and a water fountain. That combination of protection and connection was a catalyst for many breakthrough innovations during this period and was evident across many areas of study such as architecture, art and science.

An excellent example of the use of natural shapes was the symmetric polygonal shapes that pre-dated the principle of quasicrystaline geometry by 500 years, which is still being used by scientists to better understand quasicrystals at the atomic level.

This desire to design and construct something that has taken thousands of years to explain scientifically and design without modern technology is one of those ancient mysteries that baffled scholars. It only became clearer in 1984, when an American biologist took a radical and interdisciplinary approach to explain how these innovations could have been achieved.

Edward Wilson suggested the theory that humans were driven to seek connections with nature and other life forms. That was the birth of the term “biophilia” or literally, “the love of life” as we understand it today. This theory integrated architecture and physiology, propagating a new way to conceptualize the design of our build environments and their impact on our physical, social, intellectual and physiological well-being.

Using this new interdisciplinary lens that expanded our historical review of buildings beyond an architecture perspective, studies have concluded that while the term is new, the concept existed in the ancient world, dating back to those Hanging Gardens of Babylon.

What the studies have also demonstrated, but anyone who is standing in a mountain meadow with a gentle breeze ruffling tree leaves and a burbling stream nearby already knows, is that humans crave a natural connection. We simply do better physically and mentally outside the urbanized environments we have developed and closer to the natural environments from which we came.

So, how do you apply thousands of years of history, scientific study, and your own personal experience to your own home? The second part of our blog will give you the context to do that. Look for it shortly.